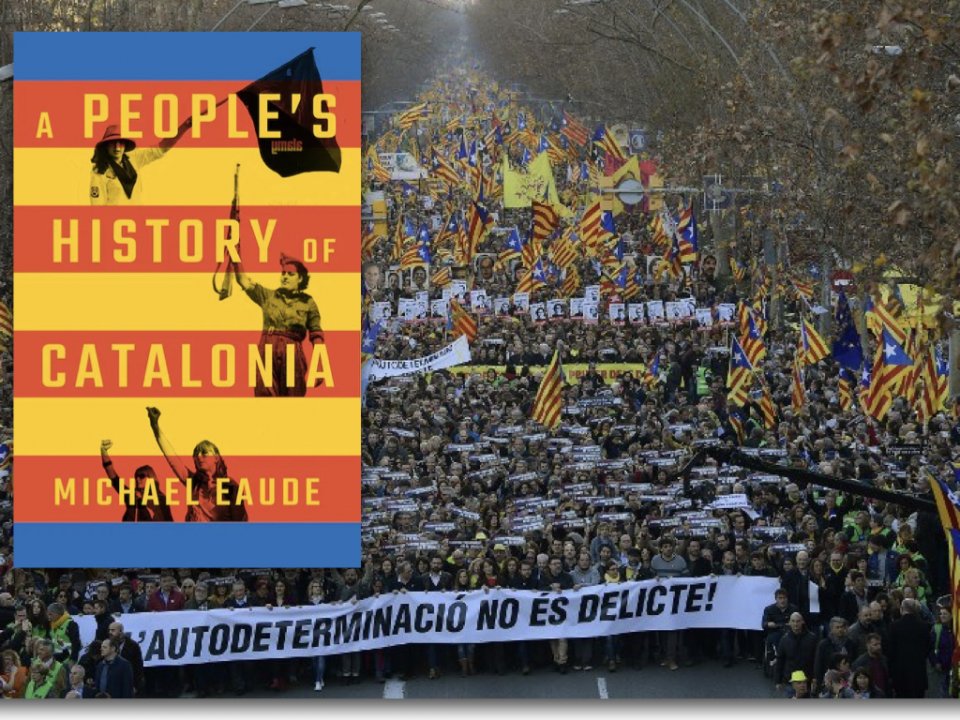

That there is no love lost between Catalonia and Spain is common knowledge. Many people are aware of the centuries’ old antagonism, and Catalonia’s struggle for independence has been especially visible since the 2017 referendum. So, when Michael Eaude opens his book with this …

‘Authors should explain their prejudice. I’ll opt for the late actor Pepe Rubianes’ succinct summary of the Catalan question: “A mi, la unidad de España me suda la polla por delante y por detras.” A polite translation might be: “I don’t give two fucks for the unity of Spain.”

… no one can accuse him of sitting on the fence.

From here, Eaude proceeds to give a detailed and well-written account of the history of Catalonia from the 10th century to the current day. He takes us on a revolutionary ride through its glory days as part of the Crown of Aragon when Catalan rule reached Athens (albeit briefly) and Sicily, the Reapers’ War, the siege of Barcelona in 1714, through the horrific mess of the Spanish Civil War, and up to the recent shenanigans of Puigdemont and his cohorts.

The story is told with an emphasis on the working class or the peasantry, and the role they have played in Catalonia’s various unsuccessful struggles for independence. And for the most part, Eaude neatly pulls off the trick of showing that much of ‘the Catalan independence movement is driven from below by its radical currents’.

There are bandits as class warriors, anarchists plotting the downfall of the system and subsequently enduring their own, peasants with scythes fighting off Castilian knights on horseback. Revolutions, uprisings, wars, wars, and more wars. For a small nation, it’s a story of epic proportions, often with calamitous consequences.

‘It is hard to see the faces and the behaviour of the poor so many centuries ago, as their voices and feelings are unrecorded. Just sometimes, an action pokes up above time past’s anonymity,’ he writes. Eaude’s ability to document these actions brings the pages to life, and his series of short rebel portraits which include people as different as the bandit Joan de Serrallonga, the anarchist Teresa Claramunt and the singer Lluis Llach, give the story cara i ulls. As the Catalans say: eyes and faces.

The book also reveals that much of this people’s tumultuous history has been plagued with contradictions, infighting, unsurmountable difficulties, and a surprising afán to back the wrong king in a fight.

In 1641, when Pau Claris declared what was to be one of Catalonia’s various short-lived republics, he did so by making French King Louis XIII the ‘Count of Barcelona’. Since when does a republic swear allegiance to a king? During another uprising, the revolt of the barretines, the cry was ‘Long live the king! Death to bad government’, and in 1714, Barcelona fatally chose the Hapsburgs over the Bourbons. They have been paying ever since.

Occasionally, the red and yellow striped spectacles through which Eaude views the Catalan story, sometimes leads him to make presumptions about peoples’ historical motives which comes across with the slightly hollow ring of Catalan ‘victimisme’. A trait that leads Catalan nationalists to confuse genuine grievances with imaginary hatred.

For example, when describing Prime Minister Olivares’ well-documented repression in Catalonia in the 17th century he says, ‘Catalans could see how Spanish over-spending on foreign wars had ruined its own backyard , Castille, plunging most of its inhabitants into poverty. Now Olivares wanted not only to do away with Catalonia’s historic rights, but also reduce it to the same condition as Castille.’ As if the then prime minister’s ambition was to impoverish the whole country he was trying to unite in a riot of nihilistic abandon.

Or when he describes the late president of Catalonia Pascal Maragall’s plans for Catalonia to form part of a federal Spain as ‘just an abstraction to draw people away from independence’. Far from being an ‘abstraction’, this was an idea that Maragall held close to his heart and tried to put into practice with the Catalan statute of 2006. The fact that the project was a failure, and was subsequently butchered by the Spanish constitutional court, does not mean it was engendered as an ‘abstract distraction’ with an ulterior motive.

Despite this, he isn’t afraid to broach the nastier parts of Catalan history. He talks about ERC’s racism toward Spanish immigrants in the early part of the twentieth century, Catalonia’s part in the slave trade, as well as the corruption of the revered nationalist president Jordi Pujol. When I put the book down, it left me with the impression that although Catalonia has never been a nation state in the modern sense of the word, despite various bloody attempts, its history provides compelling arguments for why it has every right to continue to strive to become one.

A People’s History of Catalonia, by Michael Eaude is published by Pluto Press.

Ryan Chandler is the author of Us with Us, Cadaqués. It all happened but might not be true. ALSO READ: Book review: ‘Us with Us’ – a year long sojourn in Cadaqués.

If you would like to write a review of a specific book related to Spain, please email: editorial@spainenglish.com

Sign up for the FREE Weekly Newsletter from Spain in English.

Please support Spain in English with a donation.

Click here to get your business activity or services listed on our DIRECTORY.