Many moons ago, when I was teaching at Duke University, I used to banter with my friend Allen Josephs (University of Florida) as to who would be the first to discover the cave that Ernest Hemingway portrays in For Whom the Bell Tolls.

As he usually did in his novels, Hemingway based his fiction on reality, on the Spanish Civil War confrontation he himself had reported as a journalist in the Guadarrama mountains, 50 miles northwest of Madrid.

Although Hemingway wrote his famous novel two years later in his home in Idaho, he was careful to surround himself with maps of the area in which the battle took place, thus grounding his fiction in the reality he knew so well.

We can therefore follow the footsteps of Robert Jordan as he receives his orders to blow the bridge from a Soviet General in El Escorial, or as he ascends the Puerto de Navacerrada to start his trek into enemy territory or as he descends the gorge of the Eresma river, where he sketches in his notebook the bridge itself and the points at which dynamite is to be placed to achieve a perfect blow-up.

It is easy to follow the footsteps of Hemingway’s hero in the Guadarramas except for one crucial location which is harder to determine.

To carry out his mission, Jordan had to obtain the support of a group of guerrilla warriors fighting for the Republic who had set their camp in a cave not too far from the bridge he was supposed to destroy. This cave becomes a crucial element in Hemingway’s story, since it is the scenario not only of the preparation for the attack on the bridge, but also the scenario for heated discussions on the war itself, the confrontation of ideas that divided Spaniards not only into two camps, but split those supporting the Republic into different groups: communists, anarchists, liberals etc.

The cave is the scenario for heated political discussion but also for personal confrontations. Pablo, who leads the guerrilla fighters, is confronted by Robert Jordan who has come to the cave to carry out orders from the Military Headquarters of the Republic, regardless of the way his attack would affect the men living in the cave. Soon, however, Jordan finds an ally in Pilar, Pablo’s wife, who is quick to understand the significance of Jordan’s mission. And Maria, a young Spanish girl living with the guerrilla fighters, will soon be attracted to the American Brigade leader.

The cave – and not the bridge – is the emotional and political hub around which the novel revolves, and so it was essential for Allen Josephs and for myself to locate this cave in the Guadarrama mountains.

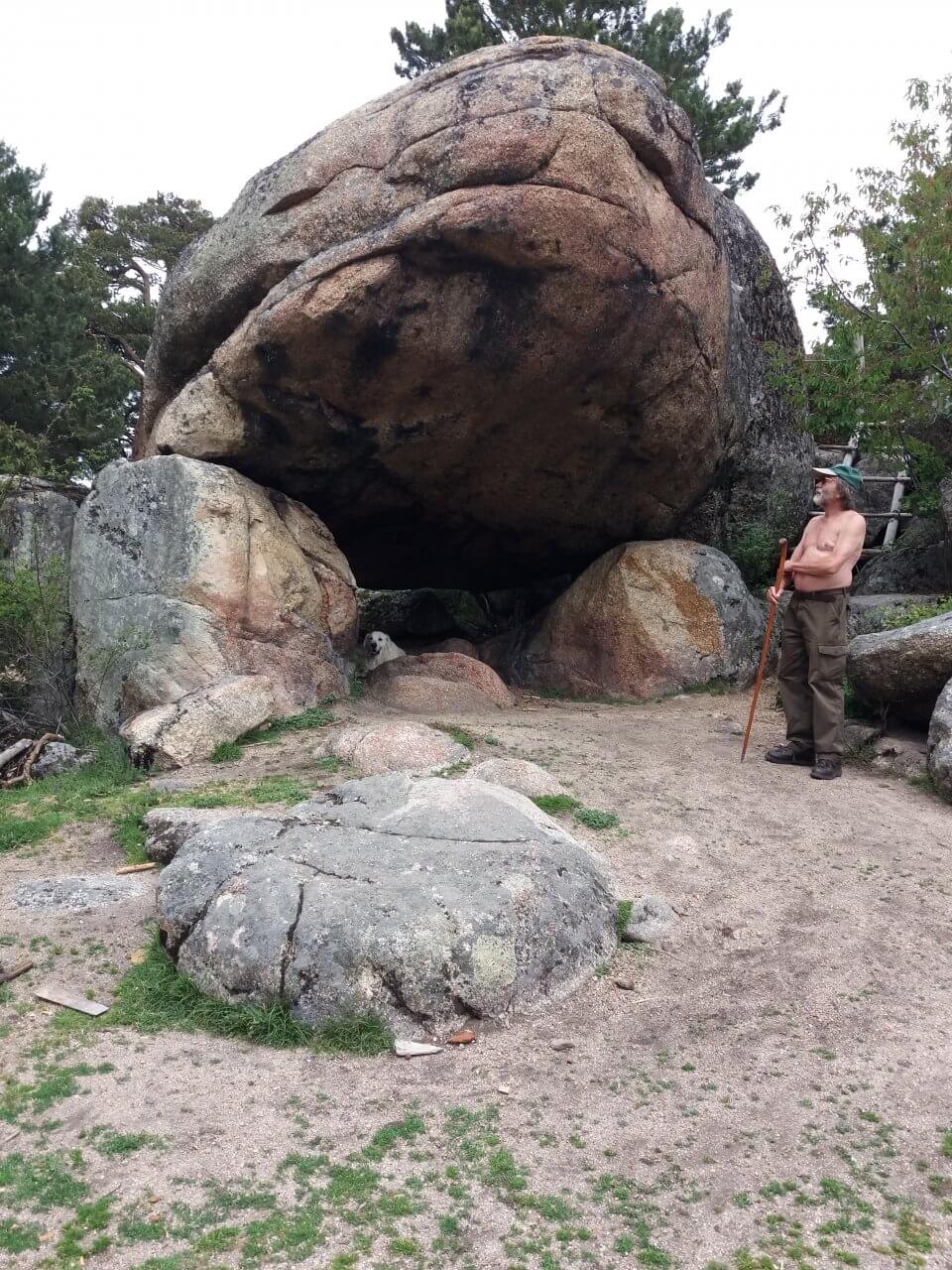

Both of us were aware that the rock formations in the Guadarrama are largely granite stone, hardly permeable for water to mould cave formations. Caves are frequent in calcarean and karstic rock formations but rare in areas where granite prevails. So, it was a surprise for us to find that there was a cave up in the mountains behind the Eresma river.

The topographic maps of the Spanish army carry the name of a cave – Cueva del Monje – which Hemingway himself must have come across when he scoured these maps to help him write his novel.

Accompanied by Jim Denza – another Hemingway freak – we ascended the mountains behind Valsaín in search of the famous cave.

The ‘Monk’s Cave’ is made up of huge slabs of granite stone which collapsed on top of one another, probably following an earthquake which occurred millions of years ago. The cave itself is unlike the one Hemingway describes in his novel, which probably indicates that Hemingway himself never saw it. He simply noted its location in the maps he was looking at to help him describe the preparation and attack on the bridge at the end of his story.

The ‘Monk’s Cave’ is not too far from La Granja, a town which had fallen to Franco. This would seem to agree with Hemingway’s remarks about the guerrilla fighters crossing the lines at night and slipping into La Granja in search of female company or simply a pack of cigarettes. Crossing the lines was a feature of daily life in the Spanish war since the front lines often divided towns and villages which were in close proximity.

The cave and the territory around it is where Hemingway stages the most moving episodes in his novel.

The Guadarrama mountains can help us re-create the story Hemingway wrote, can make the story come alive in our minds, can help us understand exactly what was going on in his novel, can introduce us to warfare not simply as the scourge of humanity but also as the awakening of the human spirit when confronted with violence.

Being alive is not something we take for granted in the midst of combat. Confronting death can be a means to understanding life, as Hemingway suggests in his novel.

The term ‘literary tourism‘ has become fashionable in our time. Reading Charles Dickens’ novels may be a better way to become acquainted with the city of London than Rick Steve’s guides.

Literature offers an emotional approach to our visits to cities around the world in the sense that we feel we had been there before.

Even though we didn’t know it, we had been to London when we first read Dickens and now that we walk around London as tourists we feel it was already part of our lives before we ever got there. In the same order of things, we can read volumes of history about the Spanish Civil War, but perhaps Hemingway’s novel can bring it back to life more effectively.

Whether you read Hemingway’s story in the past or have just finished reading it today, you are now ready to set off for the Guadarramas to feel the story come to life again. If you need a helping hand, please contact us at the Wellington Society webpage.

Ramón Buckley is a visiting professor in a number of American universities. He currently leads historic and literary tours in Madrid and surrounding areas.

This article first appeared in La Revista, published by the British Spanish Society.